Standing before me is a young woman, visibly distraught at having discovered the man she loves dead in his bed. She was found at the crime scene and is the only real suspect, but society loves her and wants her to walk free. How could someone so delicate do something so barbaric? But something's not right.

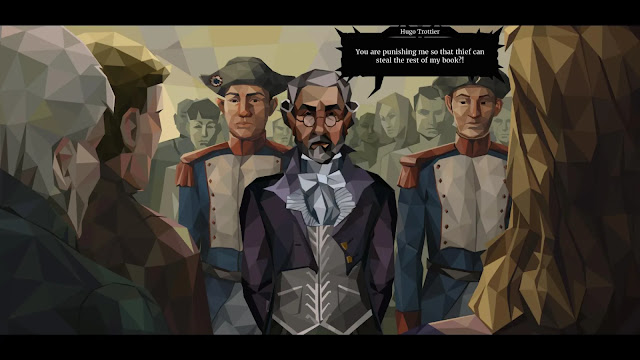

Standing before me is Citizen Capet, better known as King Louis 16th, the last king of France. He is an enemy of the Revolution and the trial feels like a formality. The decision in the hearts and minds of the fevered French public has already been made. But something's not right.

Who lives and who dies? As a judge working in the heart of the French Revolution, you decide. But the decisions are not easy - We. The Revolution makes sure of it. It delights in making you squirm. And not only is the truth elusive but the verdicts come with strings attached. Be lenient with an enemy of the revolution, whose crimes might be no more than being caught in a regime change, and the revolutionaries will hate you for it. Condemn a commoner for an act against the aristocracy, meanwhile, and the common folk will hate you for it. Then again, acquit them and the aristocracy will hate you for it.

Ignore the jury's opinion and lose support in court; ignore your family's opinion and lose support at home. Nothing exists here in isolation, and you will need to keep all elements on your side if you are to survive.

We. The Revolution measures progress in days, and on my first go I lasted just over a dozen - around four hours of game time. It's challenging, and a lot can happen in a day.

Questions you ask are unlocked via mini-game. Here, key elements from the case-notes are pulled out alongside possible categorical links - things like 'evidence', 'course of events', 'crime scene' and so on - and you have to link them up. Each success unlocks a question, but there are red herrings and you only have so many tries.

Then, you question your defendant and sometimes a witness or two, and after a few answers are given, the jury's opinion will appear on a gauge bracketed with acquittal, prison or death. The gauge rises or falls depending on the questions asked, so you can be selective and try and skew the trial one way or another if you wish. Or you can simply ignore the jury, but I wouldn't advise it. You will make enemies at court.

When you've heard enough, you open up your verdict book and select your outcome, seeing - before you wax seal and confirm it - the effect it will have on vying factions, although you won't see the effect on individual family members until you return home. When you're happy, pour and stamp your seal, and deliver your verdict. Then fill out your trial report.

A number of things can happen next. If you sentenced death, you go to the guillotine, and before you pull the rope - oh yes! - you have a chance to address the crowd. This plays out as a persuasion mini-game, which is the same for convincing individuals. It breaks arguments into segments and gives you different ways of delivering them, and success depends on how your delivery combines with their attitude. If they're withdrawn, perhaps anger will work; if they're oversensitive, maybe manipulation is the way to go. You get one dry run to see the effect of your approach before you do it for real.

Even then, the day is not over. You still need to go to the Risk-like map screen and move agent-pieces around Parisian districts to try and take control of them, earning various valuable bonuses, but there are enemy agents and wildcard factors in play too.

That's not to mention the small, turn-based battles you command, or the random events you walk into on the way home. I particularly liked the one where there was a lone, smiling decapitated head lying in the street and I decided to do nothing about it, letting the commoners have their fun. They posed for selfie-paintings with it.

In this way there is much more to We. The Revolution than meets the eye. Just when you think you have its measure it peels back another layer. You won't, I assure you, be bored (the game even shuffles new trials in, between core cases, when you replay).

But being so broad, it can't help but dilute individual parts, and the courtroom in particular suffers. There simply isn't the nuance here to deal with cases in the way you will want. Trials are fleeting affairs with one page of evidence and one witness if you're lucky, and there's very rarely - if ever - the opportunity to dig down to the truth and deliver the justice you crave.

In the case I mentioned at the beginning, for instance - the one with the young lady's bleached skull - the would-be boyfriend appears very suspicious. But the only interaction you can have with him is a paltry few questions as witness. You cannot turn the case on its head and put him on the stand, and exonerate the falsely accused.

Perhaps these are simply the restrictions of a small studio making an indie-priced game (given the scope, I can't believe its price). They are restrictions you hear in the third-rate voice over, and you read in the tangled writing, which could do with a stiff edit. It's also a game which would make a much stronger and more coherent introduction if it grounded you better in the time and place before it began. As it is, it assumes you know all about the French Revolution and the people involved in it. But I didn't, and I'm sure I'm not the only one.

Then again, We. The Revolution is a game with a poetic heart, and it looks back on a pivotal moment in human history with wit and humanity. It doesn't always add up, and it isn't always easy to follow, but when the formula clicks - when the intent and the gorgeous angular illustrative design combine - the effect can be profound.

0 Comments